About the Caring & Connected Parenting Guide

What is it? Who's it for? What does it do?

Did you know?

Children raised permissively don't mature in a healthy way

-

Learn more...

They lack self-discipline and are usually overly dependent, feel insecure, act out, and have difficulty in social situations.

Harsh Discipline leads to more behavior problems, not fewer

-

Learn more...

Harshly disciplined children are less resourceful, have poorer social skills, and lower self-esteem. They are often prone to anxiety and depression.

Neuroscience research helps us to be kind and effective parents

-

Learn more...

Babies and children are "wired" to connect with their parents. This is the key to creating a healthy, life-long bond with your child.

About Caring & Connected Parenting

It's simple; anyone can use it.

It is easy-to-read and has only 5 or 6 pages for each age group.

It makes parenting easier.

Children who are connected with their parents are naturally better behaved.

It's the foundation for a happy family.

No matter what kind of family, Caring & Connected Parenting is made for you.

Get the Caring & Connected Parenting Guide for Free

Endorsements for Caring & Connected Parenting

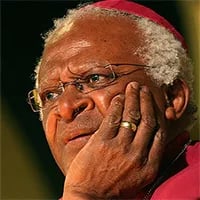

Archbishop Desmond Tutu

Nobel Peace Prize Laureate

-

Read his endorsement...

"…Parenting is no easy task, but it is the most important task with the most effect on our future. Caring and Connected Parenting will help parents achieve relationships with their children that operate on a foundation of love and mutual respect. Imagine a world in which all children feel loved and are able to share it. This is a world in which peace reigns."

-

About Desmond Tutu

Desmond Tutu, was a South African Anglican cleric who in 1984 received the Nobel Prize for Peace for his role in the opposition to apartheid in South Africa.

He passed away in 2021.

Laura Jana, M.D.

Pediatrician and Author

-

Read her endorsement...

"Parenthood is truly a life-changing event — one that can be both amazing and at the same time, daunting…there is no question that parents serve as their children’s first and most important role models. We must therefore always remember that the most valuable gift we can give our children is a consistently safe and caring environment in which they can live, learn and thrive. This easy-to-read guide helps parents do just that.."

-

About Laura Jana...

Laura A. Jana, M.D. is a pediatrician, early educator and nationally acclaimed parenting and children’s book author. She first gained national recognition working with world-renowned pediatrician Dr. Benjamin Spock and edited the 7th edition of his book. She is a member of the ReadyNation Brain Science Speakers Bureau, serves as a consultant for Primrose Schools, a 400-school system of educational child care centers, and most recently served as a strategic consultant to the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation and MIT Media Lab and is the author of over 30 books.

Daniel Siegel, M.D.

Neuroscientist and Best-Selling Author

-

Read his endorsement...

"…Caring and Connected Parenting offers adults a way to make sense of their lives and empowers them to be present with children in science-proven ways that can help cultivate resilience, focus, and resourcefulness in the next generation. Now is the time, and these are the accessible steps…"

-

About Daniel Siegel, M.D.

Daniel J. Siegel received his medical degree from Harvard University. He served as a National Institute of Mental Health Research Fellow at UCLA, studying family interactions with an emphasis on how attachment experiences influence emotions, behavior, autobiographical memory and narrative. Dr. Siegel is a clinical professor of psychiatry at the UCLA School of Medicine and the founding co-director of the Mindful Awareness Research Center at UCLA. An award-winning educator, he is a Distinguished Fellow of the American Psychiatric Association and recipient of several honorary fellowships. Dr. Siegel is also the Executive Director of the Mindsight Institute, His psychotherapy practice includes children, adolescents, adults, couples, and families. Dr. Siegel has written six parenting books, including the three New York Times bestsellers and has the ability to make complicated scientific concepts exciting and accessible to non-experts.

T. Berry Brazelton, M.D.

Professor of Pediatrics at Harvard Medical School

-

Read his endorsement...

"Today, parents and children are under more stress than they were 50 years ago when I was raising my children… This means that we must increase our efforts to support parents and children at this critical time if we want our children to have a brilliant future. When we are present to support them we can prevent problems rather than having to treat them for failure later… Caring and Connected Parenting Guide is an accessible, short, and very useful resource for all parents.."

-

About Dr. Brazelton

Thomas Berry Brazelton was an American pediatrician, author, and the developer of the Neonatal Behavioral Assessment Scale (NBAS). He hosted the cable television program What Every Baby Knows, and wrote a syndicated newspaper column. He wrote more than two hundred scholarly papers and twenty-four books. Dr. Brazelton passed away in 2018

Riane Eisler

Systems Scientist & Author

-

Read her endorsement...

"Caring and Connected Parenting gives new parents and parents from abusive backgrounds the tools necessary to connect with their children so they may develop lifelong healthy relationships. The pathway to peace—in the family and world —begins with the love and guidance of a child."

-

About Riane Eisler...

Riane Eisler is a social systems scientist, cultural historian, futurist, and attorney She is the president of the Center for Partnership Systems (CPS), dedicated to research and education, Editor-in-Chief of the Interdisciplinary Journal of Partnership Studies, an online peer-reviewed journal at the University of Minnesota that was inspired by her work, keynotes conferences nationally and internationally, has addressed the United Nations General Assembly, the U.S. Department of State, and Congressional briefings, has spoken at corporations and universities worldwide on applications of the partnership model introduced in her work, and is Distinguished Professor at Meridian University, which offers PhDs and Master’s degrees based on Eisler’s Partnership-Domination social scale.

Betty Williams

Nobel Peace Prize Laureate

-

Read her endorsement...

"This is an essential guide for parents: short, accessible, based on the latest scientific research. It is a wonderful contribution to families and an important tool to help lay foundations for a more peaceful and caring world."

-

About Betty Williams

Betty Williams was a Northern Irish peace activist best known for co-founding the Community of Peace People, an organization dedicated to promoting a peaceful resolution to the Troubles in Northern Ireland. In 1976, alongside Mairead Corrigan, she was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize for her courageous efforts in mobilizing thousands across sectarian lines to advocate for an end to violence. Williams' work was sparked by the tragic deaths of three children in Belfast, leading her to organize massive peace marches and rallies. Throughout her life, she remained committed to human rights, nonviolence, and social justice, inspiring many worldwide to pursue peace in their own communities.

Why is the Caring Connected Parenting Guide Free?

Licia Rando, author of Caring & Connected Parenting: A Guide to Raising Connected Children, is an educator, child therapist, and children's book author. She wrote this guide after two years of research on attachment, neuroscience, and interpersonal neurobiology.

During this research, Licia discovered many practices that would have helped her while raising her own children. She wanted the guide to be free because she believes all parents have the right to know how to best raise their children to be healthy, happy, caring adults.

Parenting is a difficult job that is extremely important to the health of our society. This guide will start you in the right direction of creating a loving relationship with your child that will last a lifetime.

Frequently asked questions

My children are older than four. Do you have any information that I can use?

Check out Licia's blog on this site. Many of the topics apply to older children as well.

Why is the guide free?

We believe that everyone should have access to information that can help them, not just those who can pay for it.

Can I get hard copies of the guide?

Yes, you can. We charge just enough to cover our printing and shipping costs and no more.

What can I do in return?

Just tell your friends and family about Caring & Connected Parenting and share it on social media. Encourage everyone to download a free copy.

Welcome to Caring & Connected Parenting!

Parents who are respectful and caring while providing guidance and limits raise children who successfully manage stress, school and relationships. We tend to parent the way we were parented, unfortunate news for some of us. We may have been raised in domination type families in which fear of punishment kept us obedient or overly permissive families without structure and limits. Caring & Connected Parenting, based on the latest neuroscience research, helps you create a partnership family, one in which ALL members feel cared for, valued and respected.

Contents

You as a parent

Newborn to 1 year old

1 to 2 years

2 to 3 years

3 to 4 years

More about parenting

Further reading and sources

All rights reserved

You as a parent

The past meets the present.

We tend to parent the way we were parented. To some this is great news. To others, it means painful memories of abuse, neglect or loss affect our lives with our new families. Some of us may lose control or feel unable to connect to our children.

The first step.

The first step to creating a safe, healthy home for your child is to make sense of your past and see how it may be influencing your life. Depending on the intensity of your childhood experiences, you may need profes- sional help—therapy—to make sense of things, to gain control over your actions and to heal. Get the help you need now.

If you’re having difficulty parenting, or you’re from a troubled background, see the More about parenting section toward the end of this booklet.

Learning from you.

From the time your child is born, she is watching and learning from you. You can be the type of loving, caring parent you want your child to become one day.

There is no perfect parent.

Everyone makes mistakes. The goal is to raise a child who feels loved, safe and valued—a child who cares for others and for herself.

Fathers need to be involved.

In families in which there is a father, research shows that children do better when dad is involved. A caring father’s influence may protect a child from dangers later in life, like gang violence, drug abuse and casual sex.

Children learn most when their fathers are not overly bossy or critical and let them set some direction.

Fathers who don’t make an effort to connect at these early ages may find themselves drifting away from their kids over time.

Take time away.

Primary caregivers need breaks and time away from caring to re-energize. If you have a partner, let your partner help with childcare from the begin- ning. If you are not the main caregiver, show you value the difficult job your partner is doing for your child. Honor your partner’s need for a break.

If you are a single parent, it will help to network with other parents and trade childcare to get time for your- self.

Practice calming down.

Get and give massages. Touch is calming. So is meditation. For simple meditations, see the More about parenting section.

Contents

You as a parent

Newborn to 1 year old

1 to 2 years

2 to 3 years

3 to 4 years

More about parenting

Further reading and sources

It’s the beginning of a new partnership

With the arrival of your new baby, you entered into a new partnership of learning. You’re learning to be a parent and your baby is learning . . . everything. You’re teaching each other how loving connections are made. It is your very important job to help your baby feel that she is safe—and means a lot to you!

It all starts right now.

Forming a lifelong, healthy relation- ship starts right now.

Simple things—like touching, talking with or cooing to your baby—actually affect how her brain develops!

Your caring and connected parenting protects your child’s brain from harmful stress throughout his life.

Each parent is important.

If there are two parents in the home, it’s important for your baby’s health for both parents to connect with her.

Children like the way each parent plays differently with them.

If there is violence between you and your partner—battering, insults, or yelling, this can seriously affect your child. Contact a local domestic violence agency or the National Domestic Violence Hotline at 1-800-799- 7233 www.thehotline.org.

It’s the beginning of a new partnership

With the arrival of your new baby, you entered into a new partnership of learning. You’re learning to be a parent and your baby is learning . . . everything. You’re teaching each other how loving connections are made. It is your very important job to help your baby feel that she is safe—and means a lot to you!

It all starts right now.

Forming a lifelong, healthy relation0ship starts right now.

Simple things—like touching, talking with or cooing to your baby—actually affect how her brain develops!

Your caring and connected parenting protects your child’s brain from harmful stress throughout his life.

Each parent is important.

If there are two parents in the home, it’s important for your baby’s health for both parents to connect with her.

Children like the way each parent plays differently with them.

If there is violence between you and your partner—battering, insults, or yelling, this can seriously affect your child. Contact a local domestic violence agency or the National Domestic Violence Hotline at 1-800-799- 7233 www.thehotline.org.

How to connect with your baby

Babies need touch.

Babies need touch, just like they need food. The more you touch, hold, and respond to your baby, the healthier, happier and smarter he’ll be.

Touch helps his brain develop.

It releases soothing hormones in him—and in you. Hold your baby close as often as possible. If using a baby carrier, follow the instructions carefully.

Eye contact

Look into your baby’s eyes often. It helps build a loving connection between you.

What’s your baby saying?

When your baby coos, he’s asking you to chat. When he cries, he’s asking you to feed him, keep him warm, change him or hold him—or he’s telling you he’s sick or in pain.

He is saying ‘stop what you’re doing’ if he turns away from you, cries, squirms, opens and closes his hands, pushes you, or flails his arms. Over time, you’ll learn your baby’s language.

A special personality

As your baby grows, you’ll get to know his personality. What does he like to play with? How does he calm himself? Let those who watch your baby for you know what your baby likes and dislikes.

Routines make her feel safe.

Feeling safe is good for her brain development. Follow a similar routine each day. For example, give your baby her breakfast, change her diaper, take her for a walk, play with her, take a nap, and so on.

Talk, smile and sing!

Describe what you’re doing as you’re doing it. Read aloud, catching her eye as you do.

Play every day.

Try the mirror-game: if your baby smiles, smile back; if she coos, coo back. Older babies love peeka- boo and pat-a-cake. You can let her lead the play when she’s able.

Repetition

Anything you do over and over teaches your baby “what the world is like.” Lots of angry faces or lots of smiles: what will she learn about the world from you?

“Match” your baby.

Watch your baby to see the state she’s in and approach her in the same way.

- If she’s alert and active, approach her in a playful way.

- If she’s quiet or upset, approach her quietly.

- If she startles when you speak, try a gentler way of speaking.

- If she turns away- check yourself. Are you not allowing her a break?

Newborn to 1 Year

Babies start life ready to learn.They listen to you and watch you from the moment they are born.

When parents are calm, in tune, and responsive, babies are free from stress and ready to learn about the world.

What about discipline? It’s good to know. . .

Never, ever shake a baby.

It can cause permanent brain damage and sometimes death. If you feel you might lose control, leave the baby in his crib and get help right away! Ask for help—it shows you care enough to be a good parent.

Don’t hit or yell at a baby.

Babies are needy and it can be hard to give so much.

But research shows that children who are harshly disciplined actually behave worse!

Respond in calm, loving ways and you’ll help his brain develop in a healthy way. This will make things easier for you later.

Help is available.

Having a hard time adjusting to being a parent? Get help from family, friends, neighbors or your religious community—or call a local parenting hot line.

You cannot “spoil” a baby.

Answer your baby and you show her the world is a safe place. If she cries repeatedly and you don’t answer, the stress will affect her—now and in the long term. A baby who never cries has learned that what she does doesn’t matter to anyone.

A healthy baby knows she matters; her parents show her she does—by responding to her.

If you need help right away, call

ChildHelp: 1-800-4-A-CHILD

1 (800) 422-4453

Things to do

Baby-proof your home.

Your baby is curious. He will explore as soon as he can move around, so put away the dangerous and fragile items. If you say “no” all day, your baby won’t learn by exploring. Save “no” for the dangerous things—touching stoves, chewing electrical cords.

For example, if your baby is older than seven months and chewing an electrical cord:

- Distract. Move him to another, safe object, or move the cord.

- Say “STOP!” or “NO!” if you can’t distract.

- Once you’ve said “no,” say it every time he goes near the cord.

- Wait a bit before soothing him so he learns the limit is real. Then hug away!

At nine months to one year, your baby is starting to understand “no” and he’ll test you to learn the limits. He’ll look at you before he reaches for the cord.

This is normal! Be consistent and calm. You’ll do this over and over and he will eventually learn. Later on, you may even see him pause as he goes to touch or shake his head and say “No cord!” Praise him for learning!

Get in the rhythm.

Help your baby learn the rhythms of the day. Do quiet things before bedtime. Nighttime feedings should be quiet, with low light, to help her learn day from night.

Keep a fairly regular schedule with older babies, with meals and bedtime at about the same time each day.

Make a routine that leads to bedtime, such as tooth brushing, washing, story time, feeding, massage and bed. This helps baby’s brain set up rhythms.

She’s not “manipulating” you.

If she drops a toy from the high chair over and over, she’s experiment- ing. She’s asking, “What happens to this toy when I drop it and what happens to my daddy when I drop this toy?”

At around five months old, a baby may cry to get you to come play with her. She is learning to communicate.

Instead of answering every single cry, you can sometimes give her something to entertain herself.

The magic of distraction

If she pulls your hair, you can say “no pulling”—and distract her with a toy.

Bumps in the road

Depression

If you just can’t seem to smile, play with or respond to your baby, you could be suffering from depression. If it lasts over two weeks, get professional help— for your health and your baby’s.

Many new moms feel this way. You are not to blame and with help, you will feel better. Call Postpartum Support International for information at 1-800-944-4773.

Babies can read a lack of interest in your voice, body movements and expressions. A repeated lack of interest from you can affect your baby’s development.

Massage your baby and have someone give you massages as well. Touch has amazing power.

Child care

Find a qualified person who will follow your connected and loving parenting style.

Try to ease your baby into care, especially if you begin during the “stranger anxiety” stage, which can start at five months.

When you’re home with your baby at the end of the day, sit with her and connect.

Television and screens

The American Academy of Pediatrics advises that children two years old and under shouldn’t watch television or other screens. Children need to connect with you and screens costs them valuable brain-development time and may expose them to frightening images.

Sleep

It can be difficult for you to get enough sleep, but this stage won’t last forever. Some parents wake their baby to feed right before they themselves go to bed to get a larger block of sleep. During the day, nap when the baby naps.

At around four months, babies will begin to sleep for longer periods during the night. They will start to rouse and lightly cry at certain times during their sleep cycle, but, if given a chance, may learn to soothe themselves back to sleep.

A baby left to ‘cry it out’ will feel deserted and this is not healthy.

By six months, you may be able to let him soothe himself to sleep or, if need be, pat his back and quietly tell him it’s bedtime. If you get him up repeatedly, you make yourself part of his soothing needs and he might not be able to go back to sleep without your help.

(See the Further reading and sources section at the end for more information.)

Is it colic or just fussiness?

Fussiness happens.

Babies from three weeks to three months old often have a fussy period at the end of each day.

Stay calm—it’s not your fault.

Try a pacifier and swaddling. Also hold your baby in a side or stomach position while swaying and shushing in her ear. Still crying?

You can calmly feed or change your baby to assure yourself there’s nothing else you can do.

Is it colic?

Colic, on the other hand, is crying that goes on and on and does not stop in spite of what you try. One of every ten babies can have colic. It can last up to four months but it will end. No one knows what causes it.

Ways to deal with colic.

Limit the noises in your home. Try to make it calm for yourself and the baby.

Colicky babies sometimes pull up their legs and pass gas. If you’re breast-feeding, try taking milk, caffeine and gassy foods out of your diet. If you’re bottle feeding, ask your doctor about switching formulas.

Place the baby on your lap with her belly down and gently rub her back. Or try wrapping your baby snugly in a blanket, then holding and rocking her.

Move your baby using a baby swing, stroller or car. Use massage— it will soothe both of you.

| More ways to soothe a crying baby | |

| Burping | Playing soft music |

| Swaddling | Rubbing, patting, stroking |

| Riding in car | Rhythmic noise and vibration |

| Singing, talking | Walking with baby in your arms, body sack or carriage |

| Rocking, swaying | Warm baths soothe some babies |

| Source: The American Academy of Pediatrics | |

Contents

You as a parent

Newborn to 1 year old

1 to 2 years

2 to 3 years

3 to 4 years

More about parenting

Further reading and sources

Connecting equals brain development

How you treat your baby influences how her brain grows and develops.

Just as your baby’s body changes, her brain changes as she interacts with you. You need to set limits to keep her safe and to teach her.

Show your baby respect by not name-calling, laughing at or yelling at her. And don’t allow others to do these things to her. You will enjoy the same respect from her as she grows, because you’ve taught her how to be respectful.

Connect with your baby.

A connected baby grows into a child who needs less disciplining.

The more time you put in now to connect with your baby, the easier parenting will be for you later.

Your baby needs YOU to be PRESENT. He needs:

- Your eye contact and attention (your attention to phones, tablets, computers, etc. should be minimal)

- Your understanding of what he is feeling

- Responses from you that respect those feelings

Why does it matter?

Brain development means this for your baby:

- How well he will be able to handle stress and his emotions.

- If he’ll be able to form healthy relationships with others.

- How well his memory and attention span develop, which affects school success.

- How he will love and treat his own children one day.

Connecting equals brain development

How you treat your baby influences how her brain grows and develops.

Just as your baby’s body changes, her brain changes as she interacts with you. You need to set limits to keep her safe and to teach her.

Show your baby respect by not name-calling, laughing at or yelling at her. And don’t allow others to do these things to her. You will enjoy the same respect from her as she grows, because you’ve taught her how to be respectful.

Connect with your baby.

A connected baby grows into a child who needs less disciplining.

The more time you put in now to connect with your baby, the easier parenting will be for you later.

Your baby needs YOU to be PRESENT. He needs:

- Your eye contact and attention (your attention to phones, tablets, computers, etc. should be minimal)

- Your understanding of what he is feeling

- Responses from you that respect those feelings

How to connect

Look into your child’s eyes when you speak to her. Teach her the word, “eyes” and call her attention to your eyes when you speak.

Touch and cuddle with your child. A massage at bedtime helps her relax and feel your loving presence. Touch is good for you too!

Routines help with stress.

Follow the same bedtime routine each night. For example, bathe, brush teeth, read a book and sing a lullaby. Keep meal and nap times close to the same time every day.

Sit down on the floor with your child and play. It shows her she matters to you. Relax, have fun.

Respect your child’s feelings.

Watch your child to learn how she is feeling. If she is in a quiet mood, be the same way when you approach or speak to her.

Let her release energy by taking her outside or to a playground. Children have lots of energy. To expect them to sit still for too long is not fair.

Keep “NOs” to a minimum.

Make your home baby-friendly. Put away the breakable and dangerous items. You have invited this baby into your home to share it with you. Her confidence cannot handle being told NO all day.

Keep things positive.

Instead of saying what not to do, tell him what to do in simple short words: “Color on the paper,” instead of “Don’t color on the wall.” “Look at me” may work to get his attention quickly.

Praise. Say “Good job!” “Good for you!” often. Praise helps a baby feel good about himself.

Smile at your child. It lets him know that he matters to you.

Use rhythm. Sing and dance with your child. Read nursery rhymes, books that rhyme and finger plays like Itsy Bitsy Spider. Tap or make noises in simple patterns that he can copy.

Help him identify feelings.

Make faces: happy, sad and mad. When he copies your expression, say, “You look happy, (or sad or mad),” to help him know these feelings in himself.

Respond to his sounds and words.

Use the same tone of voice and follow your child’s rhythm. Encourage him to use words. Name the things you use and the things you see. The more he can say, the easier it will be for him to tell you what he needs — and for you to understand him.

A peaceful home. If there is violence between you and your partner — battering, insults or yelling, this can seriously affect your child. Contact a local domestic violence agency or the National Domestic Violence Hotline at 1-800-799- 7233 www.thehotline.org.

Let him do things for himself.

A 15-month-old can feed himself, drink from a cup and use a spoon. Skills will improve with practice. Use sippy-cups to avoid spills while he learns. Ask your child to help you with simple tasks. It may take longer, but it makes him feel capable.

What about discipline? It’s good to know. . .

Discipline is not punishment.

Discipline means “to teach.” Your child is learning self-control and you are teaching him how until he can control himself. It is normal for him to test you over and over while he is learning the rules.

About stubbornness

Children this age can be stubborn. They will say “NO!” to you.

It’s normal. Use a distraction and your sense of humor to get you through.

Young brains are for learning.

Children learn most by imitating you. Your baby imitates everything, from the way you talk on the phone to the way you handle anger. If you yell, swear or hit, she learns to yell, swear and hit. If you react in a calm, respectful way, you teach her to act calmly.

About sharing

Children at this age may share, but it’s normal for them not to share. Your baby will imitate you eventually—so share with her! Children start to share around 2½ years, but even then they don’t share all the time.

Respectful discipline

Be firm, but be kind.

Never shake. Never hit. Hitting teaches a child to hit to solve problems and shaking can SEVERELY and PERMANENTLY damage her brain.

Distract or remove your child from things you don’t want her doing. If your child is climbing up on the table say “STOP!”, scoop her up and bring her outside to play or set up cushions on the floor.

If she won’t let you change her diaper, have a special toy just for changing time to distract her— or change her standing up.

Give your child choices.

“Would you like juice or milk?” This helps her have some control and feel her independence.

To say “NO” is to set limits.

Choose the most important things to make off-limits and the most important behaviors to focus on. And do it consistently.

If your 18 month-old threatens to push the lamp over, the first time say, “If you try to push that lamp again I will pick you up and we’ll go to the kitchen.”

If she does it again, do what you said. Always be consistent and follow through. Try not to say you will do something that you can’t or won’t do.

Never threaten to hit!

Respect his love for you.

If you are leaving your child with a sitter, tell him ahead of time. Tell him you will be back. When you return, tell him you’re back.

Children this age sometimes try to get attention with negative behavior.

Give him hugs and talk to him so he will not have to do negative things to get your attention.

If you sense negative behavior is building, change the tone by taking him on your lap, rocking and having a time out together.

Avoid problems, plan ahead.

At the doctor’s office or a friend’s house, bring a travel bag full of toys, books and cereal that comes out just for these occasions. The new items will keep your child occupied for a while.

No one is perfect.

Every parent makes mistakes. Take the time to connect and discipline with respect and you and your child will both grow to be people you can be proud of.

If nothing works and you’re

afraid of what you might do

CALL: 1 (800) 422-4453

Bumps in the road

Temper tantrums

Temper tantrums begin around 15 to 18 months and continue up to three years old. Sometimes babies can’t handle not getting their way. They want to be independent, but you and the world tell them what they can’t do. Tantrums are normal. DON’T SPANK. You can stay calm. Walk away a safe distance and let the tantrum run its course or CALMLY pick up your child. Tell him, “We can’t stay in the store,” and take him to the car or outside. Ignore him until he’s finished, then say, “It’s hard when we can’t do what we want.” Pat his hair and hug him. You can be proud of your parenting.

Biting and hitting

Pick up your baby to remove him and say, “No biting. I will stop you if you can’t stop yourself.” Try giving him a teething ring to bite. Say, “Bite this. Only this.”

Overly moody or cranky child

Is he overtired, hungry, teething or sick? If so, take care of him. If not, move to a new room, try a snack or snuggle with a book. If he continues and you are at your wit’s end, remove yourself to a corner, sit, legs crossed, eyes closed, and breathe in slowly 1, 2, 3, 4; hold 1, 2, 3, 4; breathe out for 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6. Repeat as needed.

Toilet training

Don’t worry about toilet training yet. A baby’s body and mind must be ready. For signs of readiness, see the next section about 2- to 3-year olds.

Sleep

If your child has trouble falling asleep or getting back to sleep, pat her back saying, “It’s okay, I’m here. Time to sleep.” Respect her desire for you and reassure her you are there, but also set limits and set a rhythm to her day and night hours. Keep things quiet and soothing to help her until she can soothe herself to sleep. If you play with her she’ll learn that if she screams long enough you will eventually give in. See Sears, The Attachment Parenting Book in the Further reading and Sources section.

Food

Don’t battle. You can’t make a child who is seeking independence eat. Offer healthy snacks during the day. Serve finger foods and milk at meals. Stay away from junk foods and sweets.

Give yourself breaks.

Have your partner, friend or parent watch your child while you take a break. If you are on your own, connect with other parents and share care, coffee or a walk. Go in shifts.

Contents

You as a parent

Newborn to 1 year old

1 to 2 years

2 to 3 years

3 to 4 years

More about parenting

Further reading and sources

Connecting with your toddler. It’s as important as ever...

Your toddler is wondering: “Am I wanted?” “Am I lovable?” The way you respond gives him the answer, so take time to connect with him every day.

Tune in to your child.

If he is quiet, speak to him in a quiet voice. If he is involved in something, sit nearby and watch—without directing.

Look into your child’s eyes when you talk and listen to him. When you give directions or requests, ask him to look at you while you speak.

Continue with routines at bedtime and use consistent mealtimes and schedules.

Hug and kiss your child.

Play with your child, sing, dance and read books—have fun!

Let your child explore.

Children are little learning machines. Put them in old clothes and let them play with water, paint and sand.

Let your child help.

He can carry light items to set the table. This helps him feel good about himself.

Talk about feelings with her.

Name them: happy, sad, mad, hurt, excited, scared. Acknowledge them: “I see you’re mad, but I don’t want you to get hurt jumping off the couch.”

Ask your child how she feels with words or draw faces with emotions and ask her to point. Ask her to tell you what the characters in books are feeling.

Eat with your child, but don’t expect her to sit through the entire meal. Let her play nearby while you finish.

Be consistent and predictable.

If biting is not okay one day, it’s not okay the next. Have a fair and reasonable consequence, and follow through with it.

Help her learn new words.

Say the words for things she uses every day. Encourage her to use words for familiar things. “Tell me what it is you want: a cracker or some milk?” Praise her efforts.

Encourage friendships.

Find ways to let your child be with other children her age.

Admit it when you’re wrong.

Apologize if you’ve made a mistake. It teaches your child how to say sorry and that we all make mistakes. If you fight in front of the child, which is stressful to her, let her see you apologize.

Teach a task.

Break the task into small parts. Show each step slowly. Then repeat each step with her. Let her try alone with coaching. Repeat any step you need to or let it drop if it seems frustrating. Praise any success, “Good job!”

Let her think of solutions.

Turn an accident into a time to learn: “The dog’s bowl spilled. How can we clean up?”

Teach the caretaker.

If you leave your child with a caretaker, be sure he or she follows the same ways of connecting. It is important for your child to feel safe and valued.

Praise your child’s efforts.

If he picks up toys, say “Good job cleaning up!”

Use dolls or drawings to recreate an upsetting event as you describe it. Include the child’s feelings in the telling. This helps him make sense of the event, manage stress and feel understood.

Go over the events of the day with your child.

Let him help with words or movement. As he learns more words, ask him to add to the stories. It helps him make sense of what he sees and does each day.

What about discipline? It’s good to know. . .

Two-year-olds are quick and need you to watch them.

They learn by trying, but they aren’t always safe.

Take time for yourself.

You don’t have to give to your child every minute of the day. Help her to find ways to play by herself.

Hitting teaches him to hit.

Teach respect by showing your child respectful ways to handle problems.

If there is violence between you and your partner — battering, insults or yelling, this can seriously affect your child. Contact a local domestic violence agency or the National Domestic Violence Hotline at 1-800-799-7233 www.thehotline.org.

Rules and limits are good for your child. They help him to develop self-control. Be sure both parents agree on the most important rules and limits.

Discipline is guidance

Calm yourself first. Check in with your body to be sure you’re calm before you discipline.

Don’t get into arguments.

Acknowledge your child’s feelings and move on. Remember: you’re the teacher, not the two-year-old.

Distract like a magician.

“Is that your teddy over there?” you say, as you scoop up the candy with your other hand and hide it in a drawer. Lectures and nagging won’t work. Move the TV remote if it’s too tempting.

Stay connected at time-outs.

Time-outs are for calming down, not shaming. Bring him to a quiet place with books, a blanket and YOU nearby. Play soft music or sing softly in the background. You want to provide a feeling of safety for true calming to take place.

“No hitting. No hurting.”

Use short phrases for important or repeated things.

Set limits.

A 2-year-old will test your reaction. He may look at the light switch with a daring gleam in his eye. Set the limit: “Keep the light on.” If he shuts if off again say, “If you turn the light off, I will move you.” Do it. Move the chair away from the light switch as well. Be consistent.

Show him the way.

Take his hand gently and say: “Pet the kitten gently, like this.”

Label the behavior, not the child.

Never call a child “brat,” “stupid” or anything you wouldn’t want to be called. Laughing at her when she makes a mistake or scaring her on purpose (because you think it’s funny) is harmful to her.

Give warnings.

Before you start something new or leave a place say, “In five minutes, we will leave the playground. Pick the last thing you want to do before we go.” If you are leaving your child, prepare her ahead of time. Tell her when you are back.

How to calm her down.

If she’s excited, first approach in an active way then bring the energy level down. If she’s very active, have her ‘shake her sillies out’ by following your example. Slow down the pace gradually, then get on the ground and whisper, “Let’s be quiet as a rock.”

Say it, mean it, follow through.

Don’t tell your child you’ll do something that you can’t do as a consequence. If you’re too tired or too busy this time to follow through, you send confusing messages to your child.

Limit choices.

“The red shirt or the blue shirt?”

Bumps in the road

Temper tantrums and aggression

Watch from a safe distance.

If you need to protect your child, scoop her up and bring her out to the car or someplace safe.

Don’t take it personally.

Tantrums are normal. Ignore it and let it run its course. When your child has calmed down, hug her and tell her you understand how upset she is and some day she won’t need to have tantrums.

Hitting and grabbing

Talk to your child before you meet with other children. Use feeling words to go over how the other children feel when he hits them or grabs things from their hands. Tell him if he hits or takes toys you both will leave, and follow through. Remind him you’ll do it every time to help him get control until he’s able to not hit or grab himself. Praise him for sharing.

Other bumps

Crib climbing

If you use a crib:

Plan A: Make it harder to climb out; lower the mattress if you can.

Plan B: Make it easier to climb out to prevent injury; lower the rails and use cushions beneath. Make the room safe. Gate the entrance and any stairs. Have a basket of books or safe quiet toys near the bed.

Taking care of your health.

If your experiences with your child are “out of control” or you are worried about your reactions to your child, ask yourself, “Why did I do that? How did that help my child?” If the answers are troubling, talk to someone you trust or a professional. Or call a local parenting hot line.

Naps

Children at this age take one nap a day. If your child has trouble going to sleep at night or waking up, shift the nap to an earlier time, soon after lunch. When children get up from naps they can sometimes be confused. Keep things quiet and calm, hold him until the world makes sense to him again.

Night terrors

If your child thrashes and screams at night you may want to stand nearby and wait it out to be sure he is safe. Waking the child may cause more screaming.

If this happens frequently and you’re concerned, tell your child’s doctor.

Toilet training

Is your child ready?

Start toilet training when your child shows signs of readiness.

Some signs are when your child:

- Doesn’t like being wet or soiled.

- Knows she is going. She tells you, makes grunting noises or pulls at her pants.

- Stays dry for four or more hours.

- Likes to put things where they belong.

- Has stopped saying “no” to everything.

- Shows interest when you use the toilet.

- Can pull her pants up and down.

Starting toilet training.

Let your child sit on a potty chair in her clothes at first. Show how you use the toilet. Read books about a child potty training. When she is comfortable, let her sit without clothes. The next week, dump her diaper into the potty. (Try leaving the bowel movement in the potty and not flushing it away until later, when she isn’t there.) If she’s ready to try for herself, bring the potty outside or into the play area. Remind her every hour to try. Praise her when she goes.

Don’t make a big deal out of accidents.

Have your child use the potty before a nap or put a diaper or training pants on for nap and at night. If things aren’t going well or your child is worried, stop training for now. Try again in a month or two. For more on toilet training read books by T. Berry Brazelton, M.D.; they are listed in the Further Reading & Sources section.

Contents

You as a parent

Newborn to 1 year old

1 to 2 years

2 to 3 years

3 to 4 years

More about parenting

Further reading and sources

Connecting with your child

Your child loves you and wants to be with you. At the same time, he is becoming more social. Your caring and connected way with him gives him tools to form friend- ships. You can help by arranging social times and by staying caring and connected.

Affection

Children this age need affection as much as younger children. Keep massaging and snuggling. Sit close to read and tell your child you love him.

Look into your child’s eyes.

Go into the room where he is and say, “Look at me,” before you ask him to do something.

Read together.

Talk about the character’s feelings. Ask your child why he thinks the character feels this way.

Match your child.

Watch first, then approach your child with your voice and movements matching his mood: excited, calm and so on. This helps him feel understood.

Get on the floor and play.

Sometimes your child will reveal his fears or frustrations through play with toys. With this knowledge you can reassure him.

Encourage time with friends.

Help your child connect to others by finding playmates. Join library story hours, play groups, or meet other families at the park.

Teach first.

Don’t expect to see actions you haven’t taught. If you want your child to put her shoes in the closet, show her how first. Walk her through the steps until she remembers. Praise her for trying.

Who is your child becoming?

Who are her friends? What does she like and dislike? What are her thoughts and worries? She’s not exactly like you. Explore the differences.

Teach problem solving.

Your child wants ice cream every night. You tell her it’s expensive and not good to have too much junk food. Ask her, “How can we solve this problem?”

Try her suggestions if you can.

How to connect

Give your child a job.

He can set the table if you teach him how. He’ll feel his contribution has value in your family.

TIP: Practice following step-by-step directions by playing games like Simon Says.

Teach words as you go.

Teach words that fit the place— like “elephant” at the zoo. It helps him tell his story and he’ll know the words as he learns to read.

Ask about his day.

Let him draw and explain. Ask what he remembers from this day and from other days.

Encourage self-reflection.

Ask him why... “Why do you like playing this game better than that one?” “Why do you like to have her over?”

Repair mistakes.

If he spills milk, don’t yell. Ask, “What can we do to fix this?” If you make a mistake, tell your child you were wrong. If your own emotions are getting out of control, heart racing, muscles tightening, etc., it’s okay to say, “I need a few minutes and then we’ll talk about this.” Be sure to talk later when you are in control.

About feelings

Help her identify her feelings.

It helps to be aware of body signals to understand emotions. “How does your stomach feel? What is your heart doing? A fast heart beat and tight muscles might mean you’re feeling angry.”

Respect feelings.

Don’t tell her she’s not angry if she is. Say, “It’s okay to be mad at me. Our rule is no hitting, so take a deep breath and count to five. Now, let’s think of other things we can do instead of hitting.”

Express your feelings as well.

If you’re angry, it’s okay to show it, but not in a destructive way.

Nasty remarks shame your child and hurt her self-esteem. Instead, teach her how to express her anger respectfully by expressing your anger respectfully. Stick to specific comments about how her actions affect you: “I don’t like pencil sharpening here. It gets on the table then I have to clean it before dinner when I have lots of other things to do. Please sharpen over the trash can.”

A peaceful home. If there is violence between you and your partner — battering, insults or yelling, this can seriously affect your child. Contact a local domestic violence agency or the National Domestic Violence Hotline at 1-800-799-7233 www.thehotline.org.

Give respect to get respect.

Listen to the tone of voice and words you use with your child. Is it respectful, the way you would talk to a friend?

No one feels good being called bad, stupid or lazy. Your child will believe these things of herself if told them over and over.

Give time to your children.

If you’re too busy to spend time with your child each day, re-evaluate your priorities or get help. Growing brains can be harmed by neglect.

Praise his actions and efforts, not the finished product.

“Wow, you really hit that ball.” “You’re working hard at that drawing.” This way, you’re not judging or putting unreasonable demands on him. When he shows you his picture, ask him to tell you about the parts he likes.

Encourage your child.

“I know you can do it! Way to go, buddy!” Fist bumps and loving pats on the back help a child want to try new things.

What about discipline? It’s good to know. . .

Never spank, hit or shake your child.

Children at this age look older, but they still need you to keep them safe and to show them how the world works.

Catch your child being GOOD and let her know.

“I like the way you’re sharing!”

Continue to offer choices and to distract, if necessary.

If you have an active child, let her run around for a while before you start with quiet activities.

Help her regain self-control with short phrases: “Use your words,” or “Stop and breathe.”

If you say it, do it—consistently.

Only promise consequences that you can and will carry out. Keep them simple and related to the situation: “If you throw that rock, we’ll leave.” Or “After you pick up your shoes, we’ll do the puzzle together.” Say it calmly.

Repeat your messages.

“You can have your snack; please hang up your jacket first.” If your child resists or whines, say it again. “It’s snack time. Please hang up your jacket and then we’ll eat.”

Don’t get angry—just stick to the message.

Don’t reward bad behavior.

If your child makes loud noises whenever you speak on the phone, don’t hang up saying, “I have to go; she’s making lots of noise.” This rewards the noise making! When she’s quiet and waits or occupies herself, say “Good job, finding something to do while I called Grandma!” To be fair, make sure you aren’t on the phone too much.

More about giving choices.

Don’t say “Would you like to…?” when what you mean is “It’s bath time.” Follow with a choice, like “Would you like to pick your pajamas on your own or with me?”

Plan ahead. Your child needs to feel control over some things: her toys, your home, etc. When you visit another house, have her bring a toy to share. When guests come to your house, have her choose and put away a few toys she does not want to share— ahead of time.

Use arguments to teach.

Wait to let the children work things out for themselves. If they ask for help, guide them to a solution. Ask the children how they might settle the argument. Try an idea suggested.

If it isn’t working, distract them with a new activity, or separate them until they calm down. Be sure to respect both children’s feelings. They learn from you.

Give advance warning.

“We’re going to say goodbye in 10 minutes.”

About limits

Limits are okay.

You are the adult, you take the lead and set the limits. “Spoiled children are children looking for limits,” says Dr. Brazelton, a parenting expert. No household limits means stress for you both. If your child wants to play with clay, and you have company on the way, say “No.” Explain how you understand he would like to play, but you can’t have the clay mess right now. Offer him another activity. Allow him to be upset. You don’t have to punish or give in—you can let him be.

Take time to explain.

Talk to your child about why he can’t or shouldn’t do something.

Appropriate consequences.

Find respectful ways to show your child he’s gone over a limit. Have a quiet place for him to sit nearby until he calms down. Take away a privilege, such as a TV show, not a necessity, like food.

Bumps in the road

Sleeping

If your child has given up naps, try “quiet time” each day. She can lie on a mat or in bed with books and quiet toys to use. Set a timer. In the morning, have books and quiet toys for her to use.

Children can’t read clocks. Put a small lamp on a timer and tell her when the light comes on she can get out of bed and wake you up.

Aggression

Ask your child for ways she might deal with wanting to break or throw things. If she can’t think of anything, suggest safe tension relieving activities: drawing, running around or hitting a pillow.

If she kicks or hits you to get you to stop talking, stop what you’re doing and remove her for a private talk about how to treat people with respect. Don’t let disrespect go unchallenged. Calmly help her learn self-control.

Television & Screens

A child learns through imitation. More screen or TV time means less time learning about her world and connecting to you. Be sure your child watches non-violent, age-appropriate content that won’t cause nightmares. Commercials can also be harmful. Doctors recommend no more than one hour per day of screen time for this age.

Lying, cheating and stealing

Children this age have great imaginations and love fantasy play. It’s normal for them to try out lying. To overreact and call your child “a liar“ could make the problem worse. Instead, calmly state that telling the truth is important. Then help him understand why he might have lied: was he afraid? Was he making up a story? When he begins to understand the difference between fibs and truth, ask him if he can re-tell the story using the truth in place of the non-truth. It gives him a chance to correct.

Praise him for telling the truth!

Children this young aren’t experts at understanding others. Explain how the other person feels when your child cheats or steals. Explain fairness. For stealing, explain how to respect others’ belongings. Help him return the object and apologize. Pay attention and be consistent to act and explain each time.

Whining

When your child whines say, “I can’t understand whining. Speak in your usual voice.” Then go about your work. Breaking the habit of whining can take time. Be patient. Praise his attempt at a usual voice when he has been whining.

Meal times

The goal of meal times is to spend family time together (no TV). Leave power struggles out. If meals are tense, remember your own childhood to see if this may be affecting how you view the situation.

Fussiness at meals

Shop for and make meals together. Offer samples; don’t force big portions of new foods. Don’t beg or bribe with dessert. Some parents offer ONE easy, healthy alternate meal, the same one each night, for example, a peanut butter and apple sandwich. You can tell your child that’s “all there is” and it is her choice to eat. Be sure snacks and meals are healthy. See a doctor if you’re concerned about weight.

Siblings

Recognize your child’s strengths, but don’t compare her to other children or to siblings. Labeling one child “the artist,” and another “the athlete” makes it so your children won’t try. Let her skills and talents unfold as she discovers who she is.

Time-outs

Have a quiet place your child can go to when things are out of control. Play soft music or sing softly in the background. Your child needs a feeling of safety to calm down. Sit nearby. Children have short attention spans so don’t expect her to stay too long. Experts say one minute per year old, but your child may not need this long.

Toileting

Don’t jump to big boy/girl pants if your child is not ready. Use training pants instead—they are easier to pull up and down. Children will start to be dry through naps and at night when they’re ready. Some children may have bladders that aren’t ready to hold through the night or they may be deep sleepers unable to wake themselves yet. This is normal. There’s no rush.

Painful events

Death, divorce, moving etc.

People often think children can handle pain and bounce back, but pain can live inside the child and affect him throughout life. You can help your child make sense of painful situations and relieve some of the stress. Tell him the story of the event from his view point. Be sure to talk about his feelings, not your feelings or the feelings you think he should have. For example, “You changed schools and you had to leave your favorite swing behind. What things do you miss about that swing?” You can try making a book together. Your child can draw while you write the story out for him.

What's next?

After four years old. . .

The ages between birth and four are when children are at their most vulnerable. These are the years when you’re developing your parenting style and when your child is learning about himself, the world and his relationships. Your caring and connected parenting can go on through all your child’s ages, taking into account his mental and physical growth. No one’s perfect, but parenting with love and limits will give your child a healthy start as he goes on to connect with others.

Contents

You as a parent

Newborn to 1 year old

1 to 2 years

2 to 3 years

3 to 4 years

More about parenting

Further reading and sources

Especially for people who had troubled childhoods

You don’t have to repeat the past. Cycles of violence continue from generation to generation until one person makes an effort to stop them. You can be that courageous person. Your children’s and your grandchildren’s lives can be different because of you. If you have suffered abuse, neglect or loss, you are likely to need a mental health professional to help you make sense of your life.

If you need help with your parenting right away

1-800-4-A-CHILD

(1-800-422-4453)

ChildHelp: The National Child Abuse Hotline

(Toll Free • Confidential • No Caller ID)

If there is violence between you and your partner

1-800-799-7233

National Domestic Violence Hotline

www.thehotline.org

Writing down the past

Looking back can help you make sense of your feelings Answering the following questions will help you understand more about yourself. It may be hard to put words to some of the feelings you will experience, but try as best you can. Record your answers in a personal notebook. Add any thoughts you may have over time. The more you understand about yourself, the more you’ll see how your past experiences may be affecting your relationship with your family now.

- What was it like growing up? Who was in your family?

- How did you get along with your parents early in your childhood? How did the relationship evolve throughout your youth and up until the present time?

- How did your relationship with your mother and father differ and how were they similar? Are there ways in which you try to be like, or try not to be like, each of your parents?

- Did you ever feel rejected or threatened by your parents? Were there other experiences you had that felt overwhelming or traumatizing in your life, during childhood or beyond? Do any of these experiences still feel very much alive? Do they continue to influence your life?

- How did your parents discipline you as a child? What impact did that have on your childhood, and how do you feel it affects your role as a parent now?

- Do you recall your earliest separations from your parents? What was it like? Did you ever have prolonged separations from your parents?

- Did anyone significant in your life die during your childhood, or later in your life? What was that like for you at the time, and how does that loss affect you now?

- How did your parents communicate with you when you were happy and excited? Did they join with you in your enthusiasm? When you were distressed or unhappy as a child, what would happen? Did your father and mother respond differently to you during these emotional times? How?

- Was there anyone else besides your parents in your childhood that took care of you? What was that relationship like for you? What happened to those individuals? What is it like for you when you let others take care of your child now?”

- If you had difficult times during your childhood, were there positive relationships in or outside of your home that you could depend on during those times? How do you feel those connections benefited you then, and how might they help you now?

- How have your childhood experiences influenced your relation- ships with others as an adult? Do you find yourself trying not to behave in certain ways because of what happened to you as a child? Do you have patterns of behavior that you’d like to alter but have difficulty changing?

- What impact do you think your childhood has had on your adult life in general, including the ways in which you think of yourself and the ways you relate to your children? What would you like to change about the way you understand yourself and relate to others?

The above Questions for Parental Self-Reflection are used with the permission of authors Daniel J. Siegel, M.D. and Mary Hartzell, M.Ed., from their book Parenting from the Inside Out.

Learning from your answers

You can read it out loud.

After a few days, read what you have written aloud to yourself. How do your answers make you feel? How have these experiences with your parents affected how you parent or think about parenting? What do you wish your parents had done differently?

Write what you’ve learned.

Write any thoughts you have learned about yourself in your notebook.

Talk to someone you trust.

Friends or trusted clergy may help. There are many mental health professionals who have been trained to help with experiences like yours. They can help you to heal and stop being controlled by emo- tions from your past.

What can you do about it?

If some memories are hard to think about, or there are deeper issues, such as “fear of close- ness, a shameful sense of being defective, or anger at your child’s helplessness,” contact a mental health professional to get the help you need to heal yourself and raise your child in a loving and connected way.

Understanding your body.

Be aware of the signals from your body. For example, if your child spills his milk, you may feel your body starting to react—muscles tightening, heart pounding, wanting to scream. You can learn to use these as signals that it’s time to stop for the moment, calm down or leave the room. Once you are in control, guide your child calmly.

For many people, strong emotions rise and erupt quickly. For some, this can result in lashing out, swearing, yelling, or spacing out and not being present for their children.

To be a connected parent, and to discipline with respect, you need to catch yourself before you erupt. Knowing your body’s signals is an excellent way to do this.

It helps you take charge of how your emotions are expressed— and how connected you stay to your little one.

Remember:

If you can understand why and when your strongest reactions happen, you can gradually change them.

To help with understanding, take some time after you have cooled down and repaired a connection with your child to write about how each part of your body felt in the situation that set you off— like the spilled milk. Ask yourself why you reacted the way you did and write down whatever comes to mind.

A past of abuse, neglect or loss can mean memories stored in our minds that enter into our lives with our own children. It is very serious when you react to your child in a way that causes you to be full of rage, overly anxious, spaced-out, depressed, neglectful or unable to connect.

Know your triggers.

What gets you going? Is it spilling things, whining, neediness, or something else? Identify your problem areas and make a list.

Train yourself.

It’s important that you catch yourself before you become out of control. Imagine yourself in a milk-spilling (or other) situation again. Imagine your heart starting to react, your muscles tightening, etc. STOP yourself and substitute a new response or phrase. Repeat in your mind over and over until your new way of responding becomes your automatic response.

5 Steps to Self-Control

- Know your triggers. Know your triggers so you can be prepared.

- Listen to your body. Do you feel your body tensing?

- Stop yourself before you explode. Say: “I choose to stay in control.”

- Breathe in, breathe out, slowly.

- Take a time out yourself. If you feel you’re losing control, tell your child “I need a few minutes” and go to a quiet room. Tense your muscles then relax them, shake your arms and legs and tell yourself: “I’m calm. He’s a child. I’m an adult. Everything is okay.” Think about why it’s difficult for you. Make a plan to respond differently.

Once you are in control...

- Calmly state what you want. “Please get the paper towels and we’ll clean this up.”

- Reconnect with empathy. Reconnect with your child when you are calm. If you’ve made a mistake and over-reacted by yelling, tell your child you’re sorry for acting that way. Think about what your child is feeling. Let him know you understand how you must have made him feel.

- Self- reflect. Ask yourself, “Why did I do that? How did my actions teach my child how to behave? Did it hurt her or set a bad example?” Review the five steps in your mind again so you can follow through on a planned reaction.

There is no perfect parent.

We all make mistakes. Everyone gets lost at times. A caring parent keeps trying. The goal is to raise a child who feels loved, valued and safe—who cares for others as well as for herself.

Other Strategies

Get help.

Repeated intense emotional reactions can harm your child. He can feel shame, loneliness, worthlessness, and humiliation. Get professional help to understand and gain control over your emotions.

Observe and imitate.

In play groups, library hours, the park: watch other parents who set limits but treat their children with respect. Remember any positive relationships you’ve had in your life. What did you like about the way these people treated you? Is this something you can do for your child?

Let go of your tough or cool image.

Growing up in an abusive home or unhealthy school situation can leave us with masks of toughness. Some of us learn it’s okay to show tough, angry feelings but not gentle, loving feelings.

It may be embarrassing to kiss our children or tell them we love them. But let down your guard, snuggle, sing and it will feel good. People are made for this kind of love.

Use your words.

State simply what it is you want. Some parents hit to get a child’s attention. Instead, try taking a deep breath before you ask.

Take time away.

Primary caregivers need breaks and time away from caring to re-energize. If you have a partner, let your partner help with childcare from the start. If you are not the main caregiver, show you value the difficult job your partner is doing. Honor your partner’s need for time for her/himself. If you are a single parent, exchange care with another single parent.

Change one thought at a time

Some people have destructive thoughts that repeat in their minds and hurt them and the people around them. These thoughts may even be in the voice of a parent. If you have hurtful thoughts, like those listed below, take a moment to consider where the thoughts may be coming from. And realize that you have a right to change them! When you hear a harmful thought, interrupt it. Then change it—literally. Do you have these thoughts? You can change them to these.

|

Do you have these thoughts? |

You can change them to these. |

|

I am not worth anything. |

I am a worthwhile person. |

|

Nothing I do is worth anything. |

Raising a child is worthwhile. |

|

If I am myself, no one will like me. |

It’s okay to be who I am. |

|

Why bother to change things? |

Change will make me and my family healthier. |

|

My child/baby did it to hurt me. |

My child is just being a child. |

|

All people are bad. |

All people are imperfect. |

|

Everyone is out to get me. |

There are people I can trust. |

|

Only I feel this way. |

There are professionals who understand. |

|

It’s too late to change. |

I can be a loving parent. |

|

I’m “too damaged” to change. |

I can change, I can get help. |

Relaxation and meditation

Stressed or anxious?

If you are feeling stress or anxiety, go to a quiet place, drink tea, play a musical instrument or sing, talk softly, or listen to calming music.

Get and give massages.

Touch is calming. We all need it. Most libraries have how-to books on mas- sage that can get you started.

Relaxation exercises to try.

You can actually learn how to relax. These exercises can help. If you do them every day, your body will learn the cues to start relaxing. Then, even when the baby is screaming, you can call on your body to relax.

Simple meditation.

Sit in a comfortable, upright position.

Take a slow, deep breath in. Hold for 1, 2, 3, 4, then breathe out slowly, counting 1, 2, 3, 4, 5

Repeat, focusing on your breath. Keep breathing slowly in and out. Feel your belly rise with your in breath and drop with your out breath. Feel the air come into your lungs and leave your lungs. If a thought comes, notice it and let it go with your out breath. Focus on your breathing. Breathe in peace. Breathe away stress.

Relaxation Exercise.

Sit comfortably with your back straight and hands in your lap. Breathe in slowly and deeply and release your breath slowly. Focus on your breath coming in and going out.

As you breathe, tighten the muscles in your toes, hold for a moment, and then release.

Continue the same way up your body. Slowly tighten up, hold and release your calves and thighs.

Do the same for your belly, back and chest. Now focus on your arms, shoulders and neck. Now do your ears, lips, cheeks and forehead.

Keep breathing slowly. Let worries fly away with your breath as you release it. Try it with eyes open or closed.

Guided Visualization.

Think of a quiet place you like such as a park, seashore, or woods. Linger there in your mind. Breathe in the air, imagining its scent as you breathe. Let the faint sounds wash over you and tell you that you are in a safe place. Feel the ground, water, or sand in your hands. Feel the texture as it runs through your fingers and falls back to the ground. This is your special place, a safe place, where you can be strong and whole. Relax with your sounds and smells, breathing slowly in and out.

Feel your belly rise and fall as your breath moves in and out. When you are ready, take another deep breath, exhale and come back to the room. You are back in your body, feeling peaceful and know- ing you are safe and whole.

If you practice this daily, you will be able to call your special place to mind to calm yourself as needed.

Loving-kindness meditation

Sitting comfortably, breathe in and out slowly as before.

While paying attention to your breath moving slowly in and out, call to mind someone who loves you or loved you just the way you are.

Picture yourself with this person and let yourself feel the feelings you have with her/him. Let these kind and loving feelings wash over you.

Be aware that you are loved for who you are, without having to be someone else.

Let yourself feel her/his arms around you. Feel yourself rocking as your breath moves in and out. Feel your heart beating. Feel the warmth of her/his love washing over all of you.

Stay with the slow breathing and the feeling of your heart beating and imagine that the arms have become your arms and you are rocking yourself.

Feel your own love and acceptance of yourself.

Think or whisper to yourself: “I am safe. I am happy. I am lovable.”

When you are comfortable with this meditation, let thoughts of your child, your partner and others into your arms and imagine

them bathing in the love that flows from your heart.

Wish for them, “May you be safe. May you be happy. May you feel loved.”

Adapted from Jon Kabat-Zinn’s book Coming to Our Senses.

Contents

You as a parent

Newborn to 1 year old

1 to 2 years

2 to 3 years

3 to 4 years

More about parenting

Further reading and sources

Further reading

See these titles and sources marked with an *.

The Science of Parenting.

Sunderland, M., DK, 2006.

Siblings Without Rivalry.

Faber, Adele and Elaine Mazlish

Harper, 2004.

The Attachment Connection: Parenting a Secure and Confident Child Using the Science of Attachment Theory.

Newton, Ruth P.

New Harbinger Publications Inc., 2008.

CHILDREN’S BOOKS

Lots of Feelings

Shelley Rotner

Millbrook Press 2003

The Way I Feel

Janan Cain

Parenting Press, Inc. 2000

On Monday When It Rained

Cherryl Kachenmeister (Author) Tom Berthiaume (Illustrator)

Houghton Mifflin Sandpiper Books, 2001

Sources

Anthonysamy, A.& Zimmer-Gembeck, M.J. (2007). Peer status and behaviors of maltreat- ed children and their classmates in the early years of school. Child Abuse & Neglect, 31, 971-991.

Ayoub, C, et al.(2006). Cognitive and emotion- al differences in young maltreated children: A translational application of dynamic skill theory. Development and Psychopathology, 18, 679-706.

Bai, Yu, et al.(2009). Correlates and conse- quences of spanking and verbal punishment for low-income white, African American, and Mexican American toddlers. Child Development 80 (5), 1403-1420.

Banks, A. (2010). Developing the capacity to connect. Jean Baker Miller Training Institute.

Bolger, K, Patterson, C.& Kupersmidt, J.(1998). Peer relationships and self-esteem among children who have been maltreated. Child Development 69(4), 1171-1197.

*Brazelton, T. Berry. (2006). Touchpoints: Birth to 3: Your Child’s emotional and behavioral development. Cambridge: Da Capo Lifelong Books.

Cozolino, L. (2006). The Neuroscience of human relationships: Attachment and the developing social brain. New York: W. W. Norton.

Delaney, J. et al. (2008).Verbal aggressive- ness as a predictor of maternal and child behavior during playtime interactions. Human Communications Research 34 (3). 392.

Dodge, K, Bates, J. & Pettit, G. (1990). Mech- anisms in the cycle of violence. Science 250, 1678-1683.

Dodge, K. (2008). Testing an idealized dynamic cascade model of the development of serious violence in adolescence. Child Development 79, 1907-927.

Dykema, R. (2006).How your nervous system sabotages your ability to relate: An interview with Stephen Porges about his polyvagal theory. Nexus Colorado’s Holistic Journal, March/April

*Goleman, D. (2006). Emotional intelligence: Why it can matter more than IQ. 10th Anniver- sary Edition, New York: Bantam.

*Gottman, J., & Declaire, J. (1997). Raising an emotionally intelligent child. New York: Simon and Schuster.

Henricsson, L., & Rydell, A. (2004). A. Elemen- tary school children with behavior problems: Teacher child relations and self-perception. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly 50, 111-138.

Hrdy, S.,(2009). Mothers and others. Cambridge: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press.

*Jana, L., & Shu, J.(2005). Heading home with your newborn: From birth to reality. American Academy of Pediatrics.

Koenig, A., Cicchetti, D., & Rogosch, F.(2004). Moral development: The association between- maltreatment and young children’s prosocial behaviors and moral transgressions. Social Development 13, 87-106.

Main, M., & George, C. (1985).Responses of abused and disadvantaged toddlers to distress in agemates: A study in the day care setting. Developmental Psychology 21, 407-412.

Malchiodi, C.(2008). Creative interventions with traumatized children. New York: The Guilford Press.

Naparstek, B.(2004). Invisible heroes: survivors of trauma and how they heal. New York: Bantam.

*Nelsen, J., Erwin, C., & Duffy, R. (2007). Positive discipline for preschoolers: For their early years—Raising children who are responsible, respectful, and resourceful. New York: Three Rivers Press.

Pears, K., & Fisher, P. (2005). Emotion understanding and theory of mind among maltreated children in foster care: Evidence of deficits. Development and Psychopa- thology 17, 47-65.

*Perry, B. & Szalavitz, M.(2006). The Boy who was raised as a dog: And other stories from a child psychiatrist’s notebook—what traumatized children can teach us about loss, love, and healing. New York: Basic Books.

Perry , B., Hogan, L., & Marlin, S. (2000). Curiosity, pleasure and play: A neurodevel- opmental perspective. Haaeyc Advocate, June 15, 2000. Retrieved from www.ChildTrauma.org

Perry , B. Neurodevelopmental impact of child maltreatment : Implications for practice, programs and policy. Child Trauma Academy

Pollak, S.D., et al.(2000). Recognizing emotion in faces: Developmental effects of child abuse and neglect. Developmental Psychology 36, 679-688.

Porges, S. (2014, May). Connectedness as a biological imperative: Understanding trauma through the lens of the polyvagal theory. Presented at the 25th Annual Inter- national Trauma Conference, Boston, MA.